Tradition Meets Technology in Mountain Country

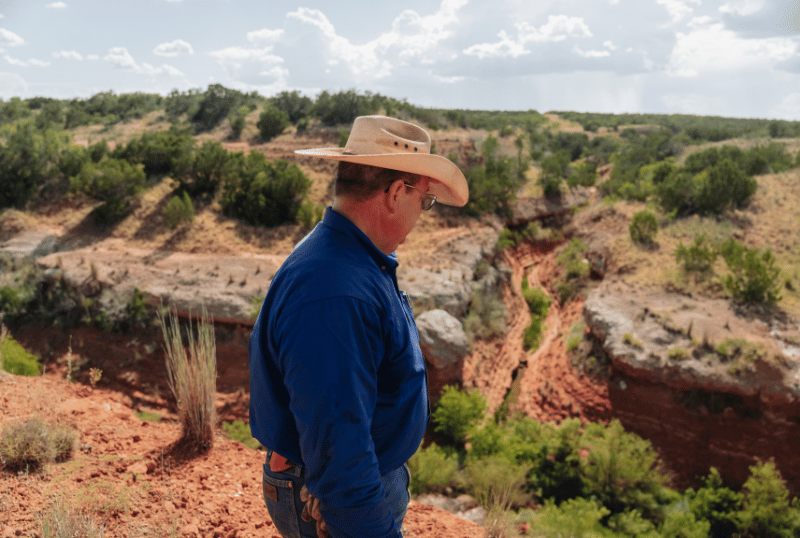

In Montana’s mountain country, where rivers cut through open range and fences rarely last a season, Cory and Jennilee Bird are rewriting what it means to manage cattle in tough terrain.

Their family has been ranching in the Missouri River Valley for more than a century, working to balance livestock, land, and wildlife across lowland pastures, forest allotments, and high summer range. Today they run nearly 600 cow-calf pairs across that landscape. For years, it meant maintaining more than a hundred miles of fence and long days making sure the herd stayed where it belonged. A single open gate or broken wire could send them miles off course and steal days of their time. Now the couple is managing the same wild country with a sense of control that once felt out of reach, and enjoying more time with their family.

When the Fence Never Lasts

In the rugged foothills of southern Montana, ranching means long days, unpredictable weather, and cattle that never seem to stay put. For Cory Bird and his family, running nearly 600 cow/calf pairs across mountain pastures and forest allotments has always come with a challenge: keeping cattle contained in country where fences never last.

At Hahn Ranch they run cattle the way it’s been done for generations: lowland pastures in spring, high mountain grazing in summer, and wintering them closer to home. The operation is a true family effort, with Cory, his wife, kids, cousins, and uncles all pitching in. But the landscape makes everything harder. Steep draws, thick brush, rivers that flood out fences, and wildlife herds that plow through wire make containment a never-ending battle.

“We maintain 112 miles of fence every year. It’s daunting,” Cory says. “The river takes it out, elk and deer run through it, and ATVs leave gates open. We’ve lost cattle to the railroad, to neighbors’ pastures—you name it. We’d waste 10 days each summer chasing cattle that got out.”

“At first I was hesitant. Putting collars on cattle sounded strange. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized it could take a lot of stress off us. We run a lot on government ground, and it’s hard to meet grazing standards when fences are always failing. I think collars are the way it’s going to be. The sooner you get into it, the better." — Cory Bird

The Search for a Better Way

The turning point came when a Forest Service range specialist introduced Cory to Nofence. The agency had already seen the technology work to protect riparian areas on public grazing lands.

“I’d never even heard of it,” Cory recalls. “At first I was hesitant. Putting collars on cattle sounded strange. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized it could take a lot of stress off us.”

Skepticism turned to action when he decided to collar a group of cattle notorious for escaping across the river. “I can’t tell you how many wrecks we’ve had there,” he says. “We took four ATVs one summer and put 36 miles on them just to gather cows that had wandered eight miles. I thought—if this technology can keep that bunch where they belong, it’s worth a try.”

“This has been the easiest summer with that group of cattle that I can remember. I don’t have to wonder where they are anymore. I can pull out my phone and know they’re not out on the railroad, not across the river, not in the neighbor’s hayfield. That’s huge. So, I’m hooked on Nofence." — Cory Bird

Knowing, Not Wondering

For Cory, the biggest win isn’t just labor savings. It’s knowing his cattle are where they are supposed to be.

“I don’t have to wonder where they are anymore. I can pull out my phone and know they’re not out on the railroad, not across the river, not in the neighbor’s hayfield. That’s huge.”

The app has already proven its worth in moments when cattle slipped a boundary. Instead of long, exhausting searches, Cory could pinpoint their location and act quickly. Collar fitting and GPS accuracy took some trial and error, but once the herd settled, Cory realized how powerful the system could be. “I’ve never herded cows from my phone before,” he says, “but one day two cows got out onto an island in the river. I set a new boundary and watched them come back across. That saved us hours of chasing.”

To make sure his virtual boundaries matched the terrain, Cory bought an extra collar that he uses to test fence lines before setting them. It lets him fine-tune the map and graze right up to features like the river’s edge with confidence. Collar fitting and GPS accuracy took some trial and error, but once the herd settled, Cory realized how powerful the system could be. “This has been the easiest summer with that group of cattle that I can remember,” he says. “So, I’m hooked on that system.”

The time savings are equally important.“Every time you’ve got a little time to go fishing with the kids or work on another project, something would come up with those cows being out. Not this year. Instead of wasting days chasing strays, we’ve had the freedom to actually enjoy summer.”

Looking Ahead

Cory is already planning to expand collars to more of his herd, especially cattle on forest allotments. “We run a lot on government ground, and it’s hard to meet grazing standards when fences are always failing. I think collars are the way it’s going to be. The sooner you get into it, the better.”

For him, Nofence is more than a tool. It’s a shift in how ranching can work in rough country. “It’s not perfect, but neither is barbed wire when the river takes it out. This gives us flexibility, saves time, and takes the chaos out of ranching. That’s worth a lot.”